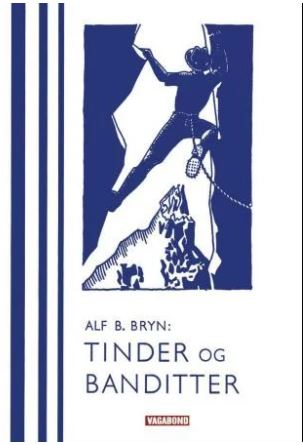

En ettermiddag i januar var jeg og tolvåringen på biblioteket for å fordrive tiden mens vi ventet på at den nyslåtte attenåringen skulle være ferdig på skolen så vi kunne gå for å spise bursdagsmiddag. Vi fant oss en ledig sofa i nærheten av reisebøkene, så da jeg begynte å kikke i hyllene for å finne noe å lese mens vi ventet var det der blikket mitt falt. Og der så jeg et kjent navn, som jeg ikke egentlig hadde forventet å finne i akkurat de hyllene. Jeg kjenner til Alf B. Bryn som forfatteren av Peter van Heeren-bøkene. Den første av disse – Peter van Heeren tar skeen i den anden haand – kom jeg over på et sånt «vi selger ut resteopplagene»-salg en gang for sikkert 30 år siden. Den serien er rett og slett fornøyelig (og nå har jeg definitivt lyst til å lese den igjen), så når det viser seg at Bryn har skrevet en bok om fjellklatring tenkte jeg at den var verdt å sjekke ut. Jeg leste nok i sofaen på biblioteket den dagen til å konstatere at jeg ville lese ferdig, så jeg lånte med meg boken hjem.

En ettermiddag i januar var jeg og tolvåringen på biblioteket for å fordrive tiden mens vi ventet på at den nyslåtte attenåringen skulle være ferdig på skolen så vi kunne gå for å spise bursdagsmiddag. Vi fant oss en ledig sofa i nærheten av reisebøkene, så da jeg begynte å kikke i hyllene for å finne noe å lese mens vi ventet var det der blikket mitt falt. Og der så jeg et kjent navn, som jeg ikke egentlig hadde forventet å finne i akkurat de hyllene. Jeg kjenner til Alf B. Bryn som forfatteren av Peter van Heeren-bøkene. Den første av disse – Peter van Heeren tar skeen i den anden haand – kom jeg over på et sånt «vi selger ut resteopplagene»-salg en gang for sikkert 30 år siden. Den serien er rett og slett fornøyelig (og nå har jeg definitivt lyst til å lese den igjen), så når det viser seg at Bryn har skrevet en bok om fjellklatring tenkte jeg at den var verdt å sjekke ut. Jeg leste nok i sofaen på biblioteket den dagen til å konstatere at jeg ville lese ferdig, så jeg lånte med meg boken hjem.

Tinder og banditter handler først og fremst om en reise Bryn foretok til Korsika i en ferie fra universitetet i Sveits, sammen med en studiekamerat fra Australia og dennes lillebror. Som intro til hovedpersonene får vi også en liten klatrehistorie fra Sveits. Det hele foregår i 1900-tallets første tiår, mens fjellklatring var noe ganske nytt (i alle fall for Europeere), og det er fullt mulig Bryn & Co var de første til å bestige noen av toppene de klatrer på Korsika. Bryn var i alle fall med på flere «førstebestigninger» i Norge, blant annet Stetind i 1910.

Fjellklatring interesserer meg bare sånn måtelig, må jeg innrømme, men Bryns fortrinn som forfatter er at han er morsom, ofte på egen bekostning.

Fra Livorno til havnebyen Bastia på Corsica tar det en 6-8 timer med båt. Det er en billig reise når man bruker dekksplass – og det gjorde George og jeg.

Båten var liten og dønningen etter en frisk nordenvind fikk den til å rulle på en måte ingen av oss likte, men vi sa ikke noe om det til hverandre.

Tvert om, da noen tid var gått uten at vi følte sikre tegn på sjøsyke, ble vi begge temmelig kjekke og fortalte sanne eller oppdiktede historier om tidligere bedrifter på bølgene.

Jeg sier sanne eller oppdiktede, fordi det jo godt kan tenkes at Georges var sanne.

(Side 52) At gutta besteg til fjellene han beskriver tviler jeg ikke egentlig på, men at fortellingen ellers inneholder noen historier som nok heller faller i kategorien «oppdiktede» har jeg sterk mistanke om.

Bryn forteller også Korsikas historie i grove trekk, også den ispedd detaljer som muligens ikke er helt sanne. Men sanne eller ikke, de er underholdende lesing:

Fra denne periode har vi en beretning om corsicanerne fra Seneca, den kjente romerske filosof, som måtte oppholde seg på Corsica som landsforvist i 8 år, visstnok fordi han hadde opptrådt overfor Messalina omtrent på samme måte som David overfor Potifars hustru.

Seneca var ikke særlig begeistret for oppholdet og omgangen.

– Hvor finner man, skriver Seneca, noe så nakent så forrevet som dette klippeland? Hvor finner man et land som er mer sparsomt med hensyn til produkter – hvor menneskene er mindre imøtekommende, hvis beliggenhet er tristere og hvis klima er mer ugjestmildt.

Og spesielt om corsicanerne uttaler han i epigramstil:

– Prima est ulcisci lex, altera vivere raptu, tertia mentiri, quarta negare deos.

– (Deres første lov er hevn, den annen å leve av rov, løgnen den tredje og Gudsfornektelse den fjerde.)

Stort sett ganske koselige egenskaper som man ser.

(Side 61) I det hele tatt var Tinder og banditter ganske fornøyelig lesing. Og nå må jeg nok grave fram noe van Heeren.

Boka har jeg lånt på Trondheim folkebibliotek.

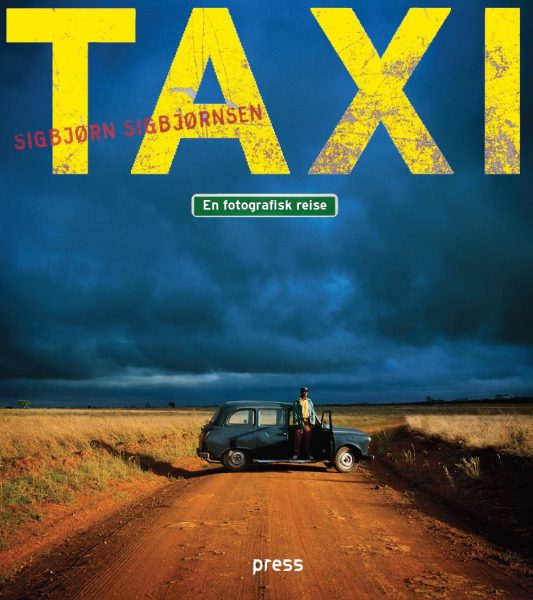

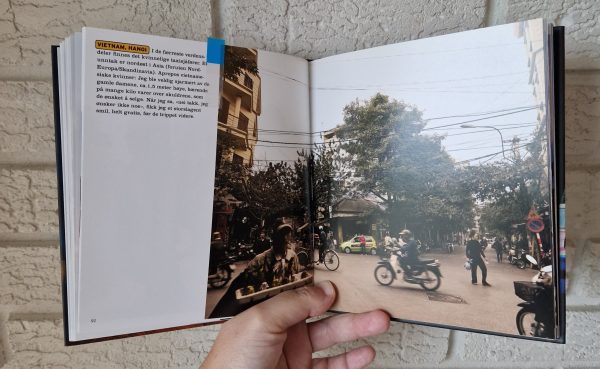

Når jeg flyttet rundt på bøker i hylla i går for å få plass til noen av bøkene jeg har arvet fra mamma og pappa sine hyller kom jeg over Taxi: En fotografisk reise av Sigbjørn Sigbjørnsen, som jeg helt hadde glemt at vi hadde på hylla. Den er lavthengende frukt for både «lese fra egne hyller» og sakprosaseptember, da det er minimalt med tekst – det er en fotobok tross alt. Men i den grad det er tekst er det jo sakprosa, så da krysser jeg av «Reise» på bingobrettet.

Når jeg flyttet rundt på bøker i hylla i går for å få plass til noen av bøkene jeg har arvet fra mamma og pappa sine hyller kom jeg over Taxi: En fotografisk reise av Sigbjørn Sigbjørnsen, som jeg helt hadde glemt at vi hadde på hylla. Den er lavthengende frukt for både «lese fra egne hyller» og sakprosaseptember, da det er minimalt med tekst – det er en fotobok tross alt. Men i den grad det er tekst er det jo sakprosa, så da krysser jeg av «Reise» på bingobrettet.

Jeg kjøpte Høyt kort tid etter at den kom ut, og hadde alle intensjoner om å lese den med en gang, men så… gjorde jeg ikke det. Man skal vel ikke stikke under en stol at selv om jeg liker tykke bøker er det litt mer tiltak å starte på en 600-sidersbok enn en 200-siders bok. Det er nok litt av forklaringen, selv om jeg vet av erfaring at Fatland skriver såpass medrivende at sidene formelig flyr av sted. Det gjør de i Høyt også, så når jeg først kom i gang tok det ikke lang tid før jeg var ferdig.

Jeg kjøpte Høyt kort tid etter at den kom ut, og hadde alle intensjoner om å lese den med en gang, men så… gjorde jeg ikke det. Man skal vel ikke stikke under en stol at selv om jeg liker tykke bøker er det litt mer tiltak å starte på en 600-sidersbok enn en 200-siders bok. Det er nok litt av forklaringen, selv om jeg vet av erfaring at Fatland skriver såpass medrivende at sidene formelig flyr av sted. Det gjør de i Høyt også, så når jeg først kom i gang tok det ikke lang tid før jeg var ferdig. After rereading 84 Charing Cross Road and the rest of the Hanff books I owned my next step was to hit Abebooks and order the ones I could find that I didn’t already own (as well as

After rereading 84 Charing Cross Road and the rest of the Hanff books I owned my next step was to hit Abebooks and order the ones I could find that I didn’t already own (as well as

The Road to Little Dribbling: More Notes from a Small Island by Bill Bryson moved swiftly to the top of my reading pile when my parents off-loaded their copy on us and was consumed within a few days of my getting my hands on it. No wonder, perhaps, Bryson being one of my favourite writers and Notes from a Small Island probably my favourite of his books. And in many respects The Road to Little Dribbling fulfills its promises. Here is the pure delight in travelling, especially by bus in Britain, that I so recognise. Here is the love for the more absurd aspects of Englishness. Here are the masses of odd little anecdotes and facts that Bryson is a master of. But I was, perhaps strangely, disappointed anyway. Partly because I have lamented the lack of Scotland in the previous volume, and here I was promised Scotland and then it turns out that England take up 355 of the book’s 381 pages, Wales (not that I mind Wales) 15 and Scotland a measly 11. And partly, well, in parts it feels a little… stale? It’s not that I didn’t like it, I did, but I guess I didn’t LOVE it. But lets think of happier things and quote a bit I do like (love):

The Road to Little Dribbling: More Notes from a Small Island by Bill Bryson moved swiftly to the top of my reading pile when my parents off-loaded their copy on us and was consumed within a few days of my getting my hands on it. No wonder, perhaps, Bryson being one of my favourite writers and Notes from a Small Island probably my favourite of his books. And in many respects The Road to Little Dribbling fulfills its promises. Here is the pure delight in travelling, especially by bus in Britain, that I so recognise. Here is the love for the more absurd aspects of Englishness. Here are the masses of odd little anecdotes and facts that Bryson is a master of. But I was, perhaps strangely, disappointed anyway. Partly because I have lamented the lack of Scotland in the previous volume, and here I was promised Scotland and then it turns out that England take up 355 of the book’s 381 pages, Wales (not that I mind Wales) 15 and Scotland a measly 11. And partly, well, in parts it feels a little… stale? It’s not that I didn’t like it, I did, but I guess I didn’t LOVE it. But lets think of happier things and quote a bit I do like (love): Peace Like a River by Leif Enger was our book circle book over Christmas, and I rather enjoyed it while reading it. However, it’s now a month later and I find I can’t really remember what was so good about it, and though the plot is pretty clear to me, the feelings it generated have not made a lasting impression. A bit of a luke-warm recommendation, then. The book circle were split in their opinions, some couldn’t finish the book, while others, like me, were more enthusiastic.

Peace Like a River by Leif Enger was our book circle book over Christmas, and I rather enjoyed it while reading it. However, it’s now a month later and I find I can’t really remember what was so good about it, and though the plot is pretty clear to me, the feelings it generated have not made a lasting impression. A bit of a luke-warm recommendation, then. The book circle were split in their opinions, some couldn’t finish the book, while others, like me, were more enthusiastic. Then for our February meeting we read The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy, and again, the reception was mixed. I found it slow to begin with, but then, suddenly, at around 120 pages, it turned a corner and after that I could hardly put it down. There is someting compelling about the way Roy takes us back and forth between past and present and the quirks of the language were wonderful, I thought.

Then for our February meeting we read The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy, and again, the reception was mixed. I found it slow to begin with, but then, suddenly, at around 120 pages, it turned a corner and after that I could hardly put it down. There is someting compelling about the way Roy takes us back and forth between past and present and the quirks of the language were wonderful, I thought.