Det er mulig det blir en trend at jeg starter å høre på lydbøker og så går over til å lese ferdig i fysisk bok, jeg har i alle fall gjort det igjen, denne gangen med den siste Alice Oseman-romanen jeg hadde på TBR, I Was Born for This.

Det er mulig det blir en trend at jeg starter å høre på lydbøker og så går over til å lese ferdig i fysisk bok, jeg har i alle fall gjort det igjen, denne gangen med den siste Alice Oseman-romanen jeg hadde på TBR, I Was Born for This.

På den annen side, kanskje det ikke blir en trend, jeg vet ikke om jeg egentlig kan høre på lydbøker på bussen, to ganger den siste uka har jeg blitt så oppslukt av boka at jeg har oppdaget akkurat litt for sent at vi hadde kommet til den bussholdeplassen jeg skulle av på, så jeg har måttet gå av på neste. Men jeg har likevel begynt på en ny lydbok, så får vi se hvordan det går.

Tilbake til Oseman: I Was Born for This har to fortellere, som bytter på å fortelle i jeg-form; Jimmy Kaga-Ricci, som er medlem av bandet The Ark, og Fereshteh Rahimi, som bruker den engelske oversettelsen av navnet sitt online – Angel – og er fan av The Ark. Boka handler først og fremst om fenomenet «fandom», men også om å være ung voksen og ikke helt vite hva man vil med livet, om «å finne seg sjæl» og om vennskap. Som vanlig i Osemans bøker er rollegalleriet mangfoldig – eller «woke» om du vil – her er det variasjon i både etnisitet, kjønnsidentitet og legning. Og variasjonen forekommer som helt selvfølgelig, samtidig som ubehagelige opplevelser med «-fober» også nevnes.

Fra et voksent synspunkt er nok det mest interessante måten Oseman klarer å belyse fandom fra mange forskjellige vinkler. Først og fremst fra perspektivet til Jimmy – som blir «shipped» med bandkameraten og bestevennen Rowan – og Angel, som føler seg middelmådig sammenlignet med sin brilliante eldre bror, sliter med vennskap IRL og fyller tomrommet med The Ark:

Mum doesn’t understand me. She doesn’t understand why I reacted so strongly about a boy band.

And I know they’re both worried about my future. They don’t ever say it, but I know they know I’m average and average is disappointing for them. Especially compared to my brother. The pinnacle of ambition and success.

Don’t worry. I know that. I’m fully aware I’m average. God, I’m so, so aware I’m average.

But I’m not going to think about any of that right now.

I don’t need to.

This week isn’t about my life.

I don’t have to think about it at all.

This week is about The Ark.

(Side 66)

Men vi får også se hvordan hyperfokuset til fansen påvirker de andre medlemmene i The Ark, og hvordan «the fandom» kan være både en livbøye og et hinder for fansen selv. Jeg liker også at Oseman trekker paralleller til Beatlemania, og dermed viser at «fandom» ikke er noe nytt, selv om internett har endret måten fansen kan interagere med hverandre og med den/de de er fan av.

Lydboka leses (eller «framføres») av to skuespillere, Aysha Kala leser Angels kapitler og Huw Parmenter Jimmys. Det er en fordel, da det gjør de to stemmene enklere å skille, når jeg gikk over til papirbok måtte jeg en gang eller to stoppe og tenke for å identifisere hvem som «snakket». Begge skuespillerne fungerer godt i rollen, med unntak av at noen av stemmene de framfører, særlig de som skal være litt eldre enn hovedpersonene (Jimmys bestefar, blant annet), bare fungerte sånn måtelig for meg, men det er en ganske liten innvending, i det store og hele kan jeg anbefale lydboka – og boka generelt.

Lydboka har jeg lånt i Libby, via Deichman, papirboka har jeg kjøpt sjøl.

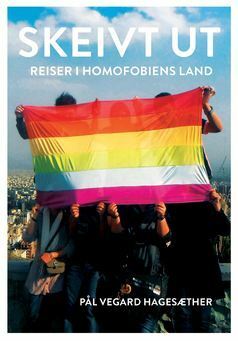

Skeivt ut kom ut i 2017, og jeg husker ikke hvor jeg hørte om boka, men den dukket nylig opp i «to-read pile»-visningen i Storygraph (en av de tingene jeg virkelig liker med Storygraph er at de viser fem tilfeldige titler fra de bøkene du har markert som «to read» på forsiden, der Goodreads bare viser de tre du sist la til), og jeg fikk det for meg å sjekke om biblioteket hadde den, og det hadde de.

Skeivt ut kom ut i 2017, og jeg husker ikke hvor jeg hørte om boka, men den dukket nylig opp i «to-read pile»-visningen i Storygraph (en av de tingene jeg virkelig liker med Storygraph er at de viser fem tilfeldige titler fra de bøkene du har markert som «to read» på forsiden, der Goodreads bare viser de tre du sist la til), og jeg fikk det for meg å sjekke om biblioteket hadde den, og det hadde de.

Jeg tok Kim Frieles bortgang i november som en påminnelse om at hun er en av de personene jeg vagt har tenkt at jeg burde lese en biografi om. Jeg var litt overrasket over at Kampene av Ola Henmo var tilgjengelig sånn uten videre på biblioteket, jeg hadde kanskje forventet at andre skulle ha fått samme idé som meg, men jeg bestilte den i alle fall til min lokale avdeling, og begynte så smått på den før jul. Så ble jeg distrahert av en gjenlesing av Pern-bøkene, deretter bestemte jeg meg for at det virkelig var på tide å lese ferdig Mitt klimaregnskap (som jeg begynte på i september!), men jeg fikk til slutt plukket Kampene opp igjen nå i januar.

Jeg tok Kim Frieles bortgang i november som en påminnelse om at hun er en av de personene jeg vagt har tenkt at jeg burde lese en biografi om. Jeg var litt overrasket over at Kampene av Ola Henmo var tilgjengelig sånn uten videre på biblioteket, jeg hadde kanskje forventet at andre skulle ha fått samme idé som meg, men jeg bestilte den i alle fall til min lokale avdeling, og begynte så smått på den før jul. Så ble jeg distrahert av en gjenlesing av Pern-bøkene, deretter bestemte jeg meg for at det virkelig var på tide å lese ferdig Mitt klimaregnskap (som jeg begynte på i september!), men jeg fikk til slutt plukket Kampene opp igjen nå i januar.