I mostly resist the temptation to buy cookbooks. Not because I don’t like them, but because I know I use them far less often than I should to justify the expense and shelf-space. And even when I do buy cookbooks, I rarely read them cover to cover. However, when I found out that the people behind the restaurant chain Dishoom (of which I have sadly only visited one location and that only once) had written a cookbook, I immediately ordered it, and over the last months I have indeed read it from cover to cover (well, ok, not ALL the ingredients lists and instructions, but a fair proportion of those as well).

I mostly resist the temptation to buy cookbooks. Not because I don’t like them, but because I know I use them far less often than I should to justify the expense and shelf-space. And even when I do buy cookbooks, I rarely read them cover to cover. However, when I found out that the people behind the restaurant chain Dishoom (of which I have sadly only visited one location and that only once) had written a cookbook, I immediately ordered it, and over the last months I have indeed read it from cover to cover (well, ok, not ALL the ingredients lists and instructions, but a fair proportion of those as well).

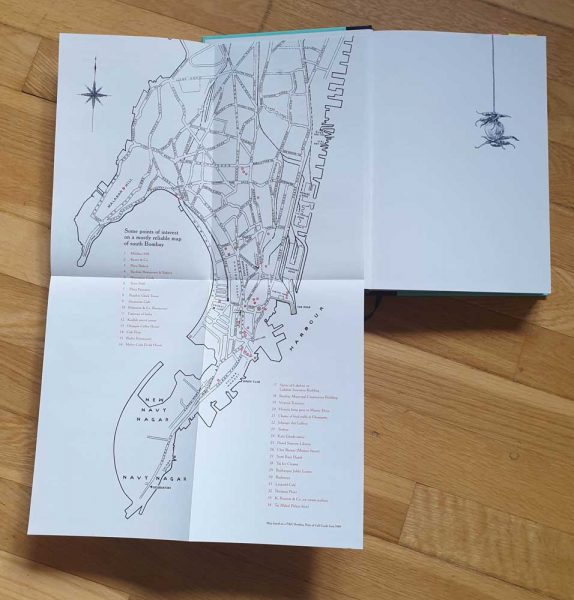

Dishoom (the book) is, as the cover says, both a «cookery book and a highly subjective guide to Bombay with map». It describes a walk around south Bombay, with stops at notable food places, from fairly fancy restaurants to street vendors’ stalls. You could probably follow along in the real south Bombay, but if you actually ate all the things they suggest in just one day I’d be impressed.

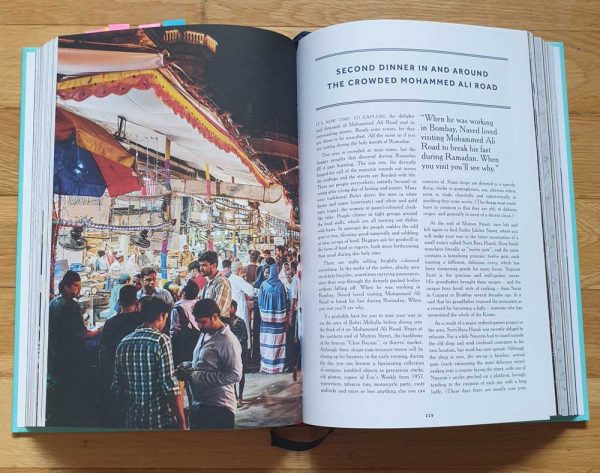

Each section of the guided tour introduces a set of recipies for a time of day, or rather a category of meals. It starts out fairly unremarkably with breakfast, mid-morning snacks and lunch, continues – with a degree of excess – with afternoon refreshments and sunset snacks, and then turns positively hobbity with first, second and third dinner, topped off with pudding and tipples.

If I ever go to Bombay, however, I will definitely try to find as many of the places mentioned as possible, but spread out over a few days…

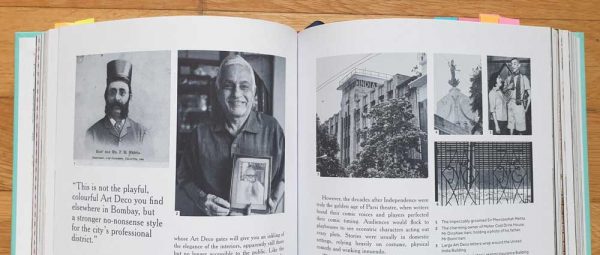

The introductory texts introduce cafés, restaurants, people and sights, and expertly evokes a feeling of place. I can easily imagine myself on the streets of Bombay as I read. I have realised over the years that I am to some extent more fond of reading books about far-away places (when well-written) than actually travelling there, and though I have an idea that I would like to visit Bombay, in reality I suspect I would dislike actually being there, not least because I am not fond of either heat or crowds. Reading about it, however, is a real pleasure.

As is custom in Bombay, the name of the road has changed several times in the hundred-odd years that this post has lingered here. Today the road bears the official post-colonial title of Netaji Subash Chandra Bose Road, though everyone knows it as Marine Drive. Such is the way with place names in Bombay. The names on your map, imposed by officialdom, have only sporadic correspondence with the names used by actual people. The worn grooves of usage take time to wear anew. VT (Victoria Terminus) will still be VT for decades to come, no doubt.

(Page 151) In addition to the guided tour parts of the book, the introductory notes for each recipe are delightful. For example: Vada Pau is described as «a simple dish, a bit like a chip butty, but obviously much better» (page 174), and reading the recipe I suspect they are correct. Chicken Tikka, however, comes with the warning:

Chicken tikka masala is supposedly Britain’s favourite dish. If it is yours, then you may be disappointed: this dish is not it.

(Page 270) And now I want both a British chicken tikka masala and the Dishoom chicken tikka, served hot, now, please.

Like many, I have read Shantaram, and was engrossed and charmed by it. It still sits on my shelf (my dad never wanted it back, he’s not a rereader), but I doubt I will ever reread it, as I doubt I’d be able to suspend disbelief sufficiently to be enchanted and engrossed again. Anyway, it’s probably not possible to write about the Iranian cafés of Bombay without mentioning Shantaram, and so Shantaram is mentioned, and summed up in such a perfect way, putting into words exactly the way I suspect I would feel if I did try to reread it:

Walk down the busy (and actually quite pleasant) Colaba Causeway towards Leopold’s, an Irani café of sorts, owned by the entrepreneurs Fahrang and Farzadh Jehani. This is the Colaba of the backpacker, the hippie, the Arab and African tourists, and they say, of the drug dealers and smugglers. It is all cheerfully fictionalised in the Bombay backpackers’ favourite novel, Shantaram, a yarn of the author’s own amazing derring-do in the city. Apparently a heroin addict convicted of armed robbery back in Australia, he escaped prison, came to India and then sat (a lot) in a glamorously seedy Leopold Café with other attractive ne’er-do-wells amongst the slowly-spinning ceiling fans, bentwood chairs and old portraits. He also worked in Bollywood, started a medical centre for slum-dwellers, was imprisioned again in a notorious local jail, and escaped to become a player in the Bombay mafia. All part of a decent mid-life gap year experience, apparently.

(Page 252) «Derring-do» is spot on, there is no better word for the main gist of the novel.

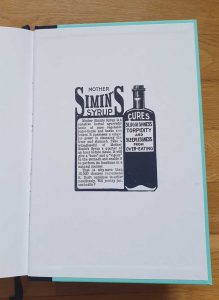

To bring focus back to the book I’m supposed to be reviewing: The photos throughout, by Haarala Hamilton (except archive photos, helpfully listed), of both places, people and food, are wonderfully evocative and support the text beautifully. My mouth waters at the food and my inner ears are assailed by the noises of a city full of cars, bicycles, people and animals. In addition, the illustrations (by Ivana Zorn) and the graphic design of the book itself are just gorgeous, and I could happily purchase this books for looks alone. The use of old newspaper advertisements are just one of the many delights.

I have yet to test any of the actual recipes, though I have bookmarked many. I did use the techniques described for «making sauces and curries» in the helpful section at the back when making a basic curry the other day, and it really did deepen the flavours of the sauce (though I think some practice is needed to avoid burning the ingredients). The instructions thoughout are clearly written, though, and amply illustrated when necessary, so once I have a free weekend I’m going to try my hand at samosas.

However, even if I never make any of the recipes in the book, it would still be something I am quite happy to have on my shelf, and if I feel the need for armchair travel to Bombay, I’ll know where to look.

Boka har jeg kjøpt sjøl.

The Road to Little Dribbling: More Notes from a Small Island by Bill Bryson moved swiftly to the top of my reading pile when my parents off-loaded their copy on us and was consumed within a few days of my getting my hands on it. No wonder, perhaps, Bryson being one of my favourite writers and Notes from a Small Island probably my favourite of his books. And in many respects The Road to Little Dribbling fulfills its promises. Here is the pure delight in travelling, especially by bus in Britain, that I so recognise. Here is the love for the more absurd aspects of Englishness. Here are the masses of odd little anecdotes and facts that Bryson is a master of. But I was, perhaps strangely, disappointed anyway. Partly because I have lamented the lack of Scotland in the previous volume, and here I was promised Scotland and then it turns out that England take up 355 of the book’s 381 pages, Wales (not that I mind Wales) 15 and Scotland a measly 11. And partly, well, in parts it feels a little… stale? It’s not that I didn’t like it, I did, but I guess I didn’t LOVE it. But lets think of happier things and quote a bit I do like (love):

The Road to Little Dribbling: More Notes from a Small Island by Bill Bryson moved swiftly to the top of my reading pile when my parents off-loaded their copy on us and was consumed within a few days of my getting my hands on it. No wonder, perhaps, Bryson being one of my favourite writers and Notes from a Small Island probably my favourite of his books. And in many respects The Road to Little Dribbling fulfills its promises. Here is the pure delight in travelling, especially by bus in Britain, that I so recognise. Here is the love for the more absurd aspects of Englishness. Here are the masses of odd little anecdotes and facts that Bryson is a master of. But I was, perhaps strangely, disappointed anyway. Partly because I have lamented the lack of Scotland in the previous volume, and here I was promised Scotland and then it turns out that England take up 355 of the book’s 381 pages, Wales (not that I mind Wales) 15 and Scotland a measly 11. And partly, well, in parts it feels a little… stale? It’s not that I didn’t like it, I did, but I guess I didn’t LOVE it. But lets think of happier things and quote a bit I do like (love): Peace Like a River by Leif Enger was our book circle book over Christmas, and I rather enjoyed it while reading it. However, it’s now a month later and I find I can’t really remember what was so good about it, and though the plot is pretty clear to me, the feelings it generated have not made a lasting impression. A bit of a luke-warm recommendation, then. The book circle were split in their opinions, some couldn’t finish the book, while others, like me, were more enthusiastic.

Peace Like a River by Leif Enger was our book circle book over Christmas, and I rather enjoyed it while reading it. However, it’s now a month later and I find I can’t really remember what was so good about it, and though the plot is pretty clear to me, the feelings it generated have not made a lasting impression. A bit of a luke-warm recommendation, then. The book circle were split in their opinions, some couldn’t finish the book, while others, like me, were more enthusiastic. Then for our February meeting we read The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy, and again, the reception was mixed. I found it slow to begin with, but then, suddenly, at around 120 pages, it turned a corner and after that I could hardly put it down. There is someting compelling about the way Roy takes us back and forth between past and present and the quirks of the language were wonderful, I thought.

Then for our February meeting we read The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy, and again, the reception was mixed. I found it slow to begin with, but then, suddenly, at around 120 pages, it turned a corner and after that I could hardly put it down. There is someting compelling about the way Roy takes us back and forth between past and present and the quirks of the language were wonderful, I thought.