There was a quote from The Mother of All Questions by Rebecca Solnit in Hvordan bli en (skandinavisk) feminist, which reminded me that I meant to read more of Solnit’s books. I enjoyed Men Explain Things to Me, even though I found it sort of patchy, so continuing with her feminist essays was a bit of a no-brainer.

There was a quote from The Mother of All Questions by Rebecca Solnit in Hvordan bli en (skandinavisk) feminist, which reminded me that I meant to read more of Solnit’s books. I enjoyed Men Explain Things to Me, even though I found it sort of patchy, so continuing with her feminist essays was a bit of a no-brainer.

And to be honest, The Mother of All Questions is better. There was not a single essay in this collection that I didn’t throughly enjoy, even if I do prefer the somewhat chatty and irreverent style of the titular «The Mother of All Questions» and of «Men Explain Lolita to Me» over the more philosophical and analytical «A Short History of Silence» and «The Pigeonholes When the Doves Have Flown», still, they are all quite excellent.

The question the title and the titular essay refers to is (of course) «why don’t you have children?» (where the you is sometimes Solnit herself, but also other childfree women). I could have quoted the whole essay, there was not a single sentence that didn’t resonate with me, though our circumstances are very different in some respects.

As it happens, there are many reasons why I don’t have children: I am very good at birth control; though I love children and adore aunthood, I also love solitude; I was raised by unhappy, unkind people, and I wanted neither to replicate their form of parentsing nor to create human beings who might feel about me the way that I sometimes felt about my begetters; the planet is unable to sustain more first-world people, and the future is very uncertain; and I really wanted to write books, which as I’ve done it is a fairly consuming vocation. I’m not dogmatic about not having kids, I might have had them under other circumstances and been fine – as I am now.

(Page 5.) Now, I do have children. But under other circumstances I might not have, and been fine. And while I find individual children charming and fascinating, I have never understood the urge to define either myself or other women solely by their status as mothers. The fact of being – or not being – a mother is hardly the most interesting thing about a person, is it? At least, I’d find it horrifying were I to meet someone where that was actually the most interesting thing about them, as I have to imagine that person as something of a blank, nondescript entity.

I gave a talk on Virginia Woolf a few years ago. During the question period that followed, the subject that seemed to most interest a number of people was whether Woolf should have had children. I answered the question dutifully (…)

What I should have said to that crowd was that our interrogation of Woolf’s reproductive status was a soporific and pointless detour from the magnificent questions her work poses. (I think at some point I said, «Fuck this shit,» which carried the same general message, and moved everyone on from the discussion.) After all, many people make babies; only one made _To the Lighthouse_ and _Three Guineas_, and we were discussing Woolf because of the latter.

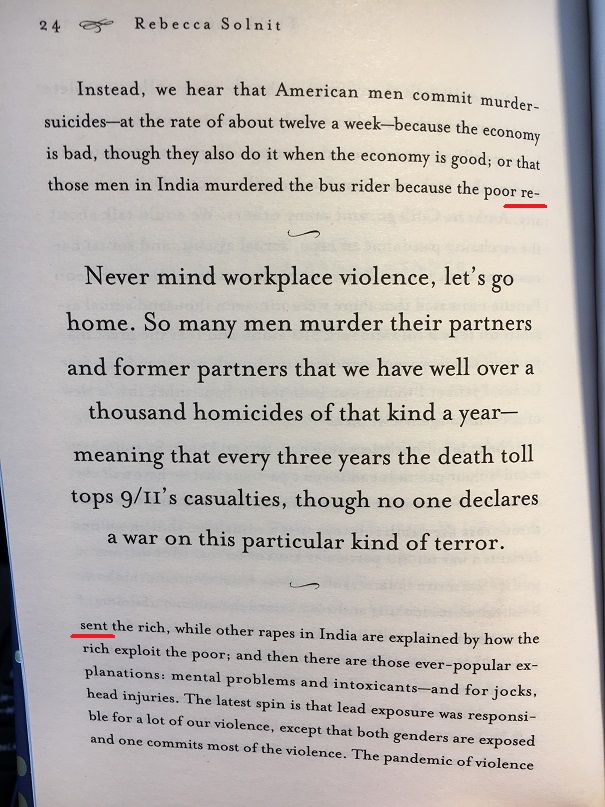

(Page 4.) In «A Short History of Silence» Solnit deals with a range of issues that all contribute to silencing women (and men), not least the violent silencing associated with rape and shame.

The pandemic of campus rape reminds us that this particular kind of crime is not committed by a group that can be dismissed as marginal in any way; fraternities at elite institutions from Vanderbilt to Stanford have been the scenes of extraordinarily vicious acts; every spring the finest universities graduate a new crop of unpunished rapists. They remind us that this deadness is at the heart of things, not the margins, that failure of empathy and respect are central, not marginal.

(Page 36.) And she writes of the non-disclosure agreements that are frequently a condition of any settlement after rape or sexual harrassment:

What does it mean when what’s supposed to be victory includes the imposition of silence? Or should we call it reimposition?

(Page 44.) After Breen, it was also refreshing to get not a SWERFy condemnation of prostitution, but rather an interesting discussion on how it is one of the topics where our neat categories are not sufficient for the purpose.

Some of the most furious debates of our time come when opposing sides insist that everything in a given category corresponds only to their version of the phenomenon. In recent debates about prostitution, one position at its most dogmatic insists that prostitutes–appearently, all prostitutes–are free agents whose lifestyle and labor choices should be respected and left alone. I’ve been aquainted with a few middle-class white sex workers. They retained control over what they did and with whom, along with the option of quitting when it stopped being what they wanted to do.

Of course that experience of being a sex worker with agency exists. So do sex trafficking and the forcing of children, immigrants, and other categories of socially and economically vunerable into prostitution. Prostitution is not a category of the enslaved or the free, but of both. How do you even speak of, let alone propose regulation of, a category as full of internal contradictions? Maybe, like so many other things, it is a language problem, and we need different terms to talk about different categories of people engaged in sex for money.

(Page 130.) In «80 Books No Woman Should Read» (a reaction essay to an Esquire article entitled «The 80 Best Books Every Man Should Read» featuring 79 books by men and 1 by a woman) Solnit points out how absurd it is that magazines like Esquire and Cosmopolitan provide (troubling) instructions on how to be A Man and A Woman respectively.

Maybe it says a lot about the fragility of gender that instructions on being the two main ones have been issued monthly for so long.

(Page 135.) And the discussion that follows about which books women should not read is very interesting indeed, and I agree with the gist of it (not having read all the authors I can’t agree with all the details). The next essay is «Men Explain Lolita to Me», and it is ever better, as it touches on the issue of «why read anything», and puts it beautifully:

This paying attention is the foundational aspect of empathy, of listening, of seeing, of imagining experiences other than one’s own, of getting out of the boundaries of one’s own experience. There’s a currently popular argument that books help us feel empathy, but if they do so they do it by helping us imagine that we are people we are not. Or to go deeper within ourselves, to be more aware of what it means to be heartbroken, or ill, or six, or ninety-six, or completely lost. Not just versions of our self rendered awsome and eternally justified and always right, living in a world in which other people only exist to help reinforce our magnificence, though those kinds of books and comic books and movies exist in abundance to cater to the male imagination. Which is a reminder that literature and are can also help us fail at empathy if it sequesters us in the Boring Old Fortress of Magnificent Me. This is why I had a nice time recently picking on a very male literary canon lined up by _Esquire_ as «80 Books Every Man Should Read,» seventy-nine of them by men. It seemed to encourage this narrowness of experience. In responding, I was arguing not that everyone should read books by ladies–though shifting the balance matters–but that maybe the whole point of reading is to be able to explore and also transcend your gender (and race and class and orientation and nationality ans moment in history and age and ability) and experience being others. Saying this upset some men. Many among that curious gender are easy to upset, and when they are upset they don’t know it. They just think you’re wrong and sometimes also evil.

(Page 142-143) Honestly, I could have quoted that whole essay from start to finish, too.

Anyway. Read this book.

Boka har jeg lånt på Trondheim Folkebibliotek.