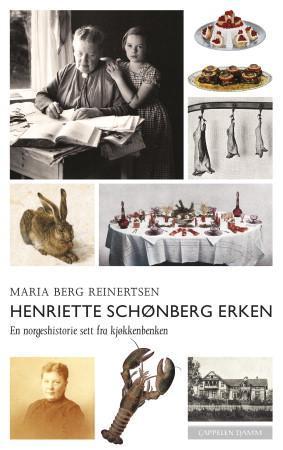

Når jeg skulle sjekke tilgjengeligheten av Maria Berg Reinertsens bok Reisen til Bretton Woods på biblioteket etter Cappelen Damms høstmøte (tilgjengeligheten var dårlig, siden boka ikke hadde kommet ut ennå, en detalj jeg hadde glemt) oppdaget jeg ikke bare at jeg selvsagt hadde lest Reinertsen før, som nevnt, men at hun i mellomtiden hadde skrevet en biografi om Henriette Schønberg Erken. Og den var tilgjengelig umiddelbart. «Perfekt!» tenkte jeg og trykket på «Reserver», jeg hadde jo mer eller mindre lovet på bokbloggertreffet at jeg skulle hive meg på biografilesesirkelen til Moshonista, og tema for oktober var «Mett (som i smør og fløte)» og hva passer da bedre? Boka var tilgjengelig og ble hentet, men selv var jeg jo stuck på tidlig 1800-tall sammen med Jack og Stephen, så det er først den siste uka jeg har fått satt meg til med Henriette.

Når jeg skulle sjekke tilgjengeligheten av Maria Berg Reinertsens bok Reisen til Bretton Woods på biblioteket etter Cappelen Damms høstmøte (tilgjengeligheten var dårlig, siden boka ikke hadde kommet ut ennå, en detalj jeg hadde glemt) oppdaget jeg ikke bare at jeg selvsagt hadde lest Reinertsen før, som nevnt, men at hun i mellomtiden hadde skrevet en biografi om Henriette Schønberg Erken. Og den var tilgjengelig umiddelbart. «Perfekt!» tenkte jeg og trykket på «Reserver», jeg hadde jo mer eller mindre lovet på bokbloggertreffet at jeg skulle hive meg på biografilesesirkelen til Moshonista, og tema for oktober var «Mett (som i smør og fløte)» og hva passer da bedre? Boka var tilgjengelig og ble hentet, men selv var jeg jo stuck på tidlig 1800-tall sammen med Jack og Stephen, så det er først den siste uka jeg har fått satt meg til med Henriette.

Henriette Schønberg Erken er ikke en av damene som har fått plass i Breen og Jordahls 60 damer du skulle ha møtt, men hun er opplagt en god kandidat til oppfølgeren 60 flere damer du skulle ha møtt (eller noe). I alle fall er hun et godt eksempel på at om man nå først skal skrive en biografi finnes det mange interessante damer å ta tak i, der man kan gjøre nybrottsarbeid i stedet for å sparke inn åpne dører med den ørtogførtiende biografien om Herr Sikkertviktigmenhvormangebiografiertrengerviomenmann.

Jeg kjøpte Schønberg Erkens Stor kokebok for større og mindre husholdninger i en faksimileutgave (av 1951-utgaven, utgitt av Aschehoug i 2008) på Mammutsalget for noen år siden, og selv om den ikke er blitt brukt (det tenker jeg jeg må gjøre noe med) har hun derfor vært på radaren min. Og portrettet Reinertsen presenterer er av en dame som utvilsomt hadde ben i nesen.

Boka er ganske finurlig bygd opp, for selv om vi i normal biografisk ånd følger Schønberg Erken kronologisk gjennom livet, er den fortellingen brutt opp ved hjelp av «munnfuller» mellom hvert kapittel, som handler mer om samtiden, om strømninger, politikk og økonomi (både makro og mikro). I tillegg starter hvert kapittel med en oppskrift hentet fra Schønberg Erkens kokebøker, en oppskrift som trekkes inn i temaet i kapittelen den introduserer. Slik blir biografien mer dynamisk enn mange andre jeg har lest, og Reinertsen kommer nærmere et svar på spørsmålet som stilles innledningsvis «Hva slags innflytelse har en bok som selger i 200 000 eksemplarer på livet til innbyggerne i et lite land?» (s. 9). Jeg blir i alle fall overbevist i løpet av boka om at husmoridealet som på sett og vis ble en klisjé på femtitallet, men som fortsatt henger over oss i dag (noe Reinertsen også er inne på) hadde sett annerledes ut om ikke Schønberg Erken hadde trosset faren og blitt hustellslærerinne i 1800-tallets siste tiår.

Det er en slags knapphet ved Reinertsens språk som jeg til å begynne med lurte på om ville gjøre boka for tørr og ensformig, men enten det skyldes den dynamiske strukturen eller at hun på tross av (eller på grunn av?) dette klarer å plassere Schønberg Erken som en faktor i samfunnsutviklingen i Norge, ble de forventningene gjort til skamme.

Henriette Schønberg Erken er et tvetydig feministisk forbilde. Selv om hun altså trosset faren («Far ville nemlig helst at vi bare skulle sitte hjemme så han kunne telle oss» s. 29), fikk seg et yrke og en karriere, og ventet med å gifte seg til hun var etablert som forfatter, kan man jo ikke med hånden på hjertet si at det å argumentere for at kvinnens viktigste rolle er å være en god husmor som (blant annet) skal holde mannen fra å drikke ved å gjøre hjemmet innbydende er noe videre kvinnefrigjørende. Og det er vel nettopp derfor hun blir en såpass fascinerende figur, den godeste Henriette.

Reinertsens framstilling oppleves basert på nitidig research og dessuten som gjennomgående redelig. Der primærkilder finnes presenteres fakta, enten det er tall eller følelser det er snakk om, men der biografen må spekulere gjøres leseren oppmerksom på nettopp at det spekuleres. Ofte fører det til at det stilles flere spørsmål enn det gis svar, men siden en av mine personlige pet-peeves er biografier (eventuelt biografiske romaner) der forfatteren skriver som om hen er tankeleser (retroaktivt, til og med) og kan presentere en forlengst død persons innerste tanker og følelser setter jeg umåtelig pris på Reinertsens framgangsmåte.

Primates: The Fearless Science of Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and Biruté Galdikas written by Jim Ottaviani and illustrated by Maris Wicks is a book I think I will get hold of a copy of to make sure it’s available for the kids.

Primates: The Fearless Science of Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and Biruté Galdikas written by Jim Ottaviani and illustrated by Maris Wicks is a book I think I will get hold of a copy of to make sure it’s available for the kids.