Better late than never, ey? I entered a bit of an unplanned blogging-holiday just as the readathon was about to end, but I guess I should summarise the latter half of the week. My last post was written Thursday afternoon, and I had realized I was never going to be able to finish with the TBR I had planned. I read Giovanni’s Room, though, and then searched about for something that might cover a few more squares. Had I remembered to check my e-reader, I could have read the memoir Once a Girl, Always a Boy by Jo Ivester which I’d purchased previously, but I didn’t (I read that a few weeks later instead). However, I suddenly remembered that I had Be Gay, Do Comics lying about unread, so that’s what I finished off my readathon with.

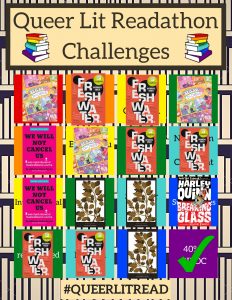

And I will argue that I actually managed to tick off every box. Giovanni’s Room obviously covers Vintage. It was also recommended to me via Twitter by @antonymet when I tweeted about the previous iteration of the readathon. And the «hot and steamy» part definitely gave me summer vibes, even if the «present» of the novel happens in a colder season. Be Gay, Do Comics contain several mini-memoirs, it definitely brought me joy, and I am happy to chose Graphic (novel/memoir/non-fiction) as my pick-my-own cathegory. Which leaves 40 % BIPOC, and since Baldwin, Emezi and brown easily make up more than 40 % of my reading, I don’t even have to start arguing for Tamaki and the various contributors to the anthology to feel like that square is solidly covered. Behold my finished bingo board:

Ok, so for some mini-reviews:

Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin was not at all what I expected. I knew next to nothing about it on beforehand, and the only other Baldwin I’ve read is Go Tell it On the Mountain, and obviously I’ve heard a lot about his autobiographical writing. So I guess I had expected something along those lines. However, the fundamentally human aspects of Baldwin’s writing are abundantly present in Giovanni’s Room as well. It is present in the older gay men that have money, but very little else going for them. They may have been young and innocent and full of hope at some point, now they are happy (though happy is definitely the wrong word) to wring whatever scraps of prentend-affection they can out of the young men who depend on them for their income. It is present, of course, in Giovanni, who is, at least at the start of the book, still young and innocent and full of hope, though penniless, and in David, who both falls hard for Giovanni and keeps him at arms’ length, because he is unable to accept the fact that he is a guy that falls for guys.

Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin was not at all what I expected. I knew next to nothing about it on beforehand, and the only other Baldwin I’ve read is Go Tell it On the Mountain, and obviously I’ve heard a lot about his autobiographical writing. So I guess I had expected something along those lines. However, the fundamentally human aspects of Baldwin’s writing are abundantly present in Giovanni’s Room as well. It is present in the older gay men that have money, but very little else going for them. They may have been young and innocent and full of hope at some point, now they are happy (though happy is definitely the wrong word) to wring whatever scraps of prentend-affection they can out of the young men who depend on them for their income. It is present, of course, in Giovanni, who is, at least at the start of the book, still young and innocent and full of hope, though penniless, and in David, who both falls hard for Giovanni and keeps him at arms’ length, because he is unable to accept the fact that he is a guy that falls for guys.

And the pleasure was never real or deep, though Giovanni smiled his humble, grateful smile and told me in as many ways as he could find how wonderful it was to have me there, how I stood, with my love and my ingenuity, between him and the dark. Each day he invited me to witness how he had changed, how love had changed him, how he worked and sang and cherished me. I was in a terrible confusion. Sometimes I thought, but this _is_ your life. Stop fighting it. Stop fighting. Or I thought, but I am happy. And he loves me. I am safe. Sometimes, when he was not near me, I thought, I will never let him touch me again. Then, when he touched me, I thought it doesn’t matter, it is only the body, it will soon be over. When it was over I lay in the dark and listened to his breathing and dreamed of the touch of hands, of Giovanni’s hands, or anybody’s hands, hands which would have the power to crush me and make me whole again.

(Page 78-79.) It is even there, and I guess that is what I found most suprising, in Hella, David’s fiance, who, by returning to Paris is the catalyst for David’s retrenching and Giovanni’s descent into tragedy.

We had been wandering about the city all day and all day Hella had been full of a subject which I had never heard her discuss at such length before: women. She claimed it was hard to be one.

‘I don’t see what’s so hard about being a woman. At least, not as long as she’s got a man.’

‘That’s just it,’ said she. ‘Hasn’t it ever struck you that that’s a sort of humiliating necessity?’

(Page 110.) I find myself less involved than I’d like to be though. Like David, I am holding all the feelings at arms’ length, though not for the same reasons (and not from choice, I may say). There is something about the love-at-first-sight (or, may I say: Lust-at-first-sight) aspect, which has never appealed to me and always leaves me feeling a little alienated. There is also the first-person narrative, which, I don’t know, I’m finding myself disliking recently. Perhaps there’s just too much of it? I can hardly remember the last book I read with an omniscient narrator, or even a third-person narrative with a singular character perspective.

I can’t really blame Baldwin for either of those, though, so don’t mind me. I am glad to have read Giovanni’s Room, but I was also quite relieved that it wasn’t longer.

Be Gay, Do Comics is a graphic anthology that I picked up after someone mentioned it on Twitter. It features more than 30 cartoonists, and contains the aforementioned mini-memoirs as well as comics about all sorts of LGBTQ+ experiences and history. They vary from the merely very good to the quite excellent, and I will be looking out for the other work of quite a few of these creators.

Be Gay, Do Comics is a graphic anthology that I picked up after someone mentioned it on Twitter. It features more than 30 cartoonists, and contains the aforementioned mini-memoirs as well as comics about all sorts of LGBTQ+ experiences and history. They vary from the merely very good to the quite excellent, and I will be looking out for the other work of quite a few of these creators.

So that was fun (again). The next week-long readathon is 5 to 11 December, but before that there is a queer lit weekend 25 to 26 September, and I might try to participate in that, too.