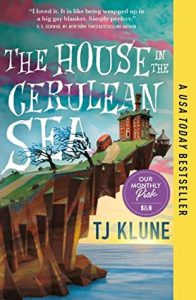

I borrowed The House in the Cerulean Sea from the library, thinking I could always purchase it later. TL;DR: I won’t.

I borrowed The House in the Cerulean Sea from the library, thinking I could always purchase it later. TL;DR: I won’t.

I apologise on beforehand, but this review is going to be a bit shouty.

I was unsure whether I would even finish the book until about three quarters of the way though, and even then it was more a case of «well, I’ve come this far» than of «I really need to know what happens!» But I did finish, I even cried a bit at the end (granted, it doesn’t take much). And I was left with a «Well, that was a rather mediocre experience, really, I’ll probably go with three stars on Goodreads.» Then I went on Goodreads and read some reviews of the book and dicovered how Klune came up with the idea for the book and my rating dropped. But let’s start with my initial reaction, taking the book at face value:

It’s definitely overly saccarine. I could overlook that, probably, found family is my absolutely favorite trope (which I admit is odd, since I actually come from a suprisingly functional family). I mean, who doesn’t love unwanted, misunderstood children finally finding a loving family?

And gay romance is a plus, even if I had a hard time actually believing in the romance (I can see what Linus sees in Arthur, the other way around: Not so much. And all his «you dear man»s dont’ convince me. However).

The «moral» of the book it’s hard to disagree with: Prejudices are bad and just because you’re different you are still worthy of love and respect. Or thereabouts. Though it is perhaps hammered home a bit too obviously (with a sugar-coated mallet). More «tell» than «show».

The fat-shaming we could have done without, also.

But the main problem is that there are too many things that don’t make sense about the society – or world – the book is set in.

The children are orphans? Lucy’s father is the Devil, for crying out loud. Are you saying the Devil was real, but now he’s dead? Are all magical children orphans? Why? And if not, what happens to those that have parents? Are they allowed to stay with them, or are there forced separations? Why are they called orphanages if some of the children have living parents? The term «orphanage» is made a point of in the book, Arthur says it’s a misnomer as «people don’t come here looking to adopt», but surely that’s not a fundamental characteristic of an orphanage? I thought an orphanage was a place where orphans lived (and Merriam-Webster agrees with me). Which they do. If they are orphans. So: Are they?

The scene where Linus first meets Extremely Upper Management (and the name «Extremely Upper Management», and, well, really, the whole setup of DICOMY, including his supervisor Mrs. Jenkins) is basically a mix of Kafka’s The Process and the hearings of the Wizengamot at their worst. Including absurd, villainesque effects like the room being dark and lights being turned on in dramatically choreographed sequence. But then, when Linus returns from the island with his recommendation that the orphanage stay open, this menacing, bureaucratic beast goes: «Ok.» And everyone lived happily ever after. WHICH IS NOT HOW THINGS WORK. And THEN he turns whistleblower and the existing management has to resign. Which makes even less sense.

And now we get to the crux of the matter: None of it makes sense in the world Klune has built, but it becomes plainly offensive when you learn that his inspiration for the book came from Canadian residential schools.

Here’s what Klune has said about it: «It remained fuzzy until I stumbled across the Sixties Scoop, something I’d never heard of before, something I’d never been taught in school (I’m American, by the way). In Canada, beginning in the 1950s and continuing through the 1980s, indigenous children were taken from their homes and families and placed into government-sanctioned facilities, such as residential schools. The goal was for primarily white, middle-class families across Canada, the US, and even Europe—to adopt these children. It’s estimated that over 20,000 indigenous children were taken, and it wasn’t until 2017 that the families of those affected reached a financial settlement with the Canadian government totaling over eight hundred million dollars.»

I’m sure if someone had turned up to one of these «schools» in the sixties and said «Uh, I don’t think you ought to kidnap, beat, starve and kill these children, actually,» the system would have been dissolved at once and everyone would have gone on to live long, prosperous, non-traumatised lives. OR NOT.

And these fictional children, that are orphans, apparently, but are based on real life indigenous children who were removed from their families and communities in state-sanctioned-kidnappings… When the book ends, they are still living in the orphanage. And I admit that in the story this sort of makes sense, especially since they are supposedly orphans, but a better, happier ending would surely have been to reunite these children with their families and communities?

So, no. I will not be needing a physical copy of this book. I will be quite happy to hand it back to the library.

Boka har jeg lånt på Trondheim folkebibliotek.